Rethinking the Sino-Tibetan Frontier

Posted: February 7, 2014 Filed under: Tibet Governance 1 CommentSeminar on Gender, Identity Politics and State-Society Relations on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier

February 3, 2014

Dr. Tenzin Jinba, Professor of Sociology and Anthropology, Lanzhou University, Gansu province; Postdoctoral candidate, Yale University

During a fieldtrip in 2010 to study language policy in eastern Tibet, I took the opportunity to travel to Gyarong, a land fabled among Tibetans for its distinctive linguistic traits and cultural character. There, as promised, I was duly struck by the extraordinary features of the Gyarong local world. The language, for instance, would take deliberate study and effort to master, even for an Amdo or Khampa Tibetan dialect speaker. The soaring stone architecture, while familiar, was decidedly a few notches more splendid than elsewhere in eastern Tibet. Perhaps most remarkably, my institutional hosts took pride in pointing out that this was a land where women were accustomed to ruling the roost.

How did these distinctive cultural characteristics play into the politics of identity among the Gyarong people? What implications did these dynamics have on state-society relations, given the location of Gyarong along the Sino-Tibetan civilizational contact zone? How might these dynamics in turn challenge us to reconsider our preconceptions about the condition of “marginality” itself?

By all rights, these questions should be regarded as standard anthropological fare. Yet in the context of contemporary Tibet, they are not. Given the tangled web of live wires that is the Tibetan region today, to raise such questions in a sustained way – to build a systematic long term research study around them – requires a bottomless reserve of pluck and tenacity.

Dr. Tenzin Jinba, professor of sociology and anthropology at Lanzhou University in Gansu, exemplifies that unlikely combination of nerve and persistence among research scholars of contemporary Tibet. In his willingness to wrestle on the page with these fraught questions of Tibetan identity politics, he has not only provided a refreshing new standpoint on the politics of ethnicity and ethnic representation in the context of Tibet, he has also thrown down the gauntlet for the debate-to-come about the collision of Tibetan and Chinese nationhood.

During his recent seminar at the Elliott School, Tenzin Jinba provided a spirited commentary on the development of his work and the publication of his recent book, In the Land of the Eastern Queendom: The Politics of Gender and Ethnicity on the Sino-Tibetan Border (University of Washington Press, 2014). Chronicling one local township’s competitive bid for the official status of the capital of what he calls “the Eastern Queendom,” the book explores the effects of tourism and commercialization, on the one hand, and the reach of the Party-state apparatus into local levels, on the other.

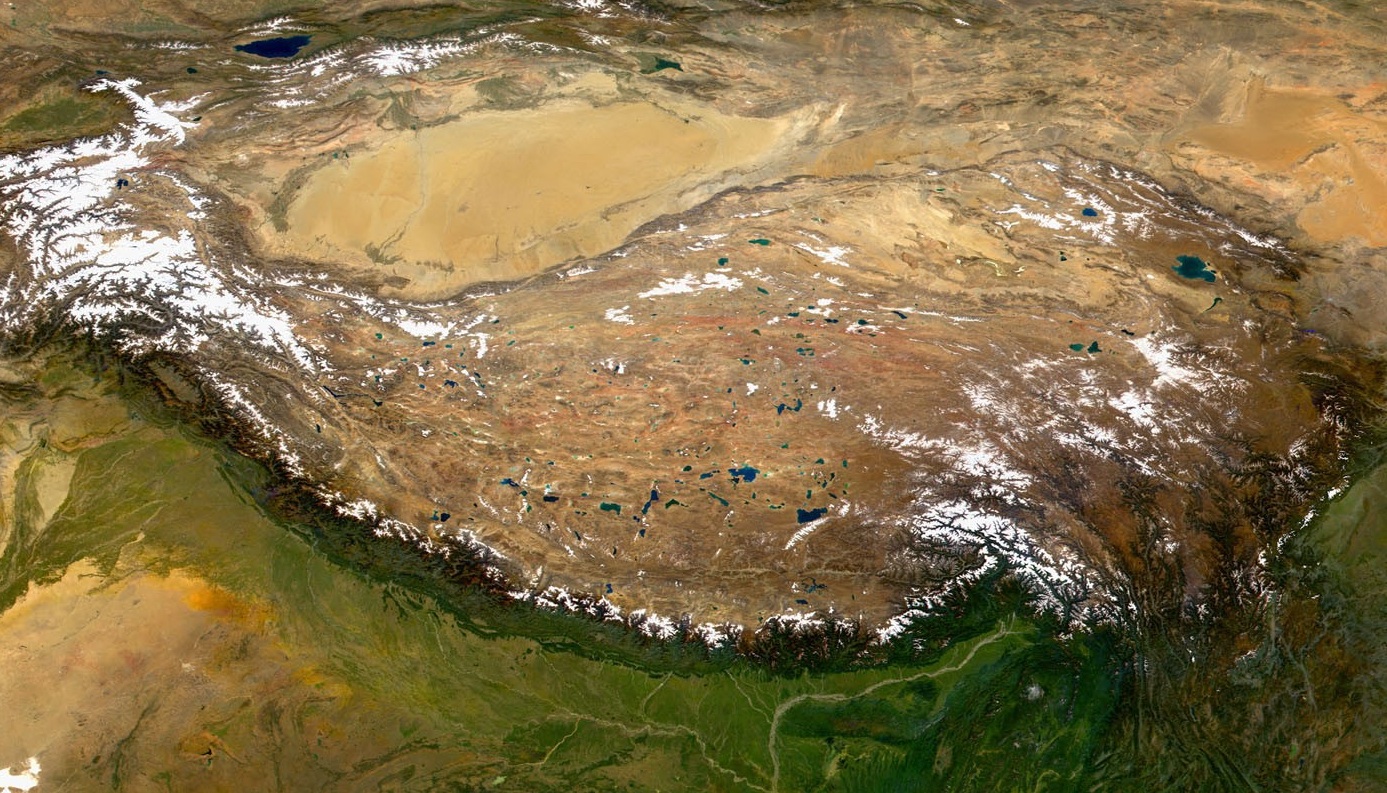

Throughout, Tenzin Jinba casts an unflinching gaze at the cultural politics of what is both his homeland and his ethnographic field. With a population of roughly 300,000, Gyarong today sits on the far eastern edge of the Tibetan plateau, much of it straddling Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefectures. The focus of his book, however, is Danba county, a fragment of the Gyarong world that somehow wound up administratively assigned to the otherwise Kham-dominated Ganzi Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture.

Caught betwixt and between these contending cultural forces, the book examines how one Gyarong county sought to manage the encroaching cultural politics of its diverse neighbors. Seen from a wide angle lens, it could be said that the tale being told is of how Gyarong has sought to adjust itself to the post-2008 Tibetan cultural order – a new order wherein much is now made of the local responses to what Tenzin Jinba delicately refers to as “the Tibetan riots of 2008.” This is no easy task. Given the high-strung atmosphere in local places across the Tibetan region, it is hard to imagine anyone but someone with Tenzin Jinba’s depth and breadth of local knowledge being capable of penetrating the wall that shields local cultural and institutional politics from external view.

Administratively, Gyarong straddles the Qiang, Aba and Ganzi Tibetan Autonomous Prefectures, Sichuan.

Perhaps most significantly, Tenzin Jinba brings back the strait-laced analytical framework of center-periphery, only to cast it aside in favor of re-imagining the periphery as a center of its own. As a people along the Sino-Tibetan border, the Gyarongwa are not only subject to the “civilizing projects” of the Tibetan and Chinese centers, they are also the subjects of their own restless creativity and local agency in defining an identity against a complex ethno-national terrain. In what he calls the convergence zone – a space where centers “coalesce, fuse and contend” – marginality can be seen as a resource. As such – and as he memorably documents in Eastern Queendom – the very idea of marginality can be mobilized for strategic use in forging a deepening awareness of a center that is always under construction, and yet always already present.

Curiously, for a study that is essentially about the politics of ethnic identification, Tenzin Jinba makes an unconventional decision in his choice of ethnonyms. Specifically, he designates the term “Zangzu” as his primary signifier for what is commonly referred to in standard English-language academic practice as “Tibetan.” Even eschewing the English terminology, he could have chosen to prioritize the native Gyarong terminology of “bo” and “bopa.” Instead, his decision to use the state bureaucratic (and Chinese-language) term of Zangzu throughout his book in reference to anything Tibetan – even coining the provocative term, “the Zangzu region” – draws conspicuous attention to that which is passed over in silence: namely, the effect of the state in shaping what is thinkable as the irreducible category of political subjectivity for those within the modern Chinese state.

Given the astuteness of Dr. Jinba’s maiden study of marginality and identity in Gyarong, the logic underlying his strategic use of ethnonyms will doubtless come to sharper light in his next project. And as his research expands into neighboring areas along this contested border region, he stands to provide an innovative foundation for the study and understanding of not just the Sino-Tibetan frontier, but of the construction of the ideas of China and Tibet as such.

Dr. Tenzin Jinba’s seminar was co-sponsored by Culture in Global Affairs (CIGA) and the Global Gender Program (GGP) at the Institute for Global and International Affars.

It was very interesting presentation at Elliott School. Thanks Tashi la for providing such opportunities for the local community and observers who are interested in learning about different issues related to Tibet from experts. It is very helpful program.

I wanted to comment a couple things on what the presenter brought up.

I thought it was funny that growing up in Tibet, I had always assumed Gyarong was as Tibet as my own area, which is more in the western part of Kham, and I had never heard of anyone questioning it’s Tibetness. Also I had never heard of anyone saying people of Gyarong were “barbarians”, the term Tenzin Jinba used quite a few times to refer what other Tibetan say/consider Gyarongwas were. Of course the sensitive issues are sensed more by the locals who are experience it and they know the reality better than outsiders. So, it is not for me to say these issues don’t exist, and I must consider these exist because he is from there. But when he used some instances of the Gyarong people not supporting Tibetan political issues as part of his examples to say Gyarong is different, I thought it didn’t work at all. I think we can find people with different opinions or choose different positions on Tibet’s political issues in every part of Tibet–even in the capitol Lhasa, which no body would say not being part of Tibet just because there might be some people who don’t support Tibetan movement.

After the presentation, someone mentioned to me that Alan Dawa Dolme, a famous singer, cried recently for not being able to speak Tibetan because she has only learned Chinese as kid.